This event is one that requires significant preparation and practice in order to get the best out of the riders. It is not simply about having the strongest time trial specialists, but working together and not against each other. Time trialists are specialists at delivering relatively consistent effort for the length of a TT, while in contrast a good team time trialist needs to deliver short, hard efforts on the front with limited recovery while in the paceline. Some thought needs to be given to: how to lap, lap length, rider strengths and rider weaknesses.

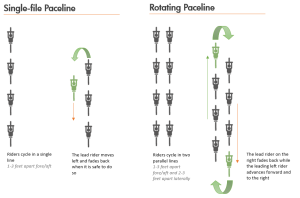

Paceline: continuous chain (rotating)

- Pros:

- riders sheltered in both lines (both in the working and recovering line

- short, intense efforts can mean faster pace

- Cons:

- harder efforts when on the front (e.g. likely 500-550w+ for a 70kg rider, for 10s for a TTT in the Tour de France). These require some effort from anaerobic metabolism and need recovery. See previous post on stage 4 on anaerobic repeatability.

- recovery is shorter (I think this is the bigger issue):

- with 9 riders x 10 seconds efforts each means 80 seconds not on the front…but it also requires another 10 second effort to get on the back of the forward moving chain too, so two 10 second efforts every 90 seconds

- with only 5 riders (time is taken on the fifth rider across the line, so you need to finish with at least 5 riders), 5 x 10 seconds efforts each means 40 seconds not on the front and 10 seconds to get on the back of the forward moving chain too, so two 10 second efforts every 50 seconds or 30 seconds “recovery”. Bear in mind it is probably still close to 300w or more when a rider is tucked in behind his team mate “recovering”.

- increased loss of distance: every time a rider pulls off the front of the paceline, you effectively lose that distance e.g. the bike length and gap to the next rider (so around two metres every time a rider ends his lap on the front – see below). This is more pronounced with shorter, and therefore more laps.

Paceline: single file, longer efforts

- Pros:

- longer efforts of around 30 seconds are likely slightly less intense (in the 450-500w range for a 70kg rider) – the reason why is because every time you hit the front there is a intense first few seconds taking over from the previous rider before settling into the effort. This is similar to the effort to get on the back after the lap too.

- longer recovery: if we look at the comparison of effort to recovery again, 30 seconds efforts on the front is balanced by four minutes of “recovery”. So counting getting back on after each effort it works out to 40 second effort, 3:50 minute “recovery”.

- with five riders it works out to 40 seconds effort and 1:50 minutes recovery

- longer efforts of around 30 seconds are likely slightly less intense (in the 450-500w range for a 70kg rider) – the reason why is because every time you hit the front there is a intense first few seconds taking over from the previous rider before settling into the effort. This is similar to the effort to get on the back after the lap too.

- Cons:

- slightly harder effort getting on the back after dropping back from the front of the paceline as there is no shelter.

Loss of distance each lap

When two teams have a rider on the front doing the same speed, the one that laps the least, will get there first. This is because every time a rider drops off the front of the paceline, you effectively lose the the length of space that rider takes up e.g. one bike length plus the gap to the next rider (approximately 2 metres). For example, a 30min TT like Stage 9:

- Short laps: a team doing 10 second laps will do 180 laps in total (30 x 6 laps per minute). If the distance a rider takes up is 2 metres then that is 180 x 2 metres or 360 metres of lost distance compared to a hypothetical team that didn’t lap at all, going the same speed while on the front (note, we are talking about speed of the rider on the front of the paceline, not average speed for the team as a unit).

- Long laps: the team that takes 30 second laps, will do 30 x 2 per minute or a total of 60 laps. This works out at 120 metres lost when a rider moves of the front of the paceline. An advantage of 240 metres from the above.

- Number of efforts: another point to consider with these two lapping styles is the number of efforts:

- the 10 second crew did a total of 180 efforts or 20 x 10 second efforts for each of the 9 riders or 36 x 10 second efforts for five riders

- the 30 second effort team did 60 efforts total or 6.667 x 30 second efforts for each of the 9 riders or 12 for five riders

- consider also that continuous chain requires a similar effort from each rider, whether they are Froome or a domestique e.g. they all spend around 10 seconds on the front (or sit on the back when tired) as compare to the group taking longer pulls (the strong riders in this group can take longer laps without disrupting the paceline).

- bear in mind, this was a short TTT, so the effect will be greater for longer distances.

- If a rider feels strong, the rule of thumb is to take longer laps and not to increase the pace. The pace is adjusted more broadly based on how the team as a whole is performing/feeling.

Conclusions

- Generally speaking it becomes more efficient to take longer laps the less riders there are in the group or team. If there were only two riders (e.g in a two up TT or a breakaway) then one minute or longer may be appropriate. It seems the “recovery” part of the paceline may well be more important than the effort. The pace should be smooth and even, with the stronger riders taking longer laps, not faster ones.

- Pace and efforts will be dictated by the weakest rider you need to keep (the fifth rider in this case). Avoid accelerations that might drop them or put them on the limit.

- For any team a coach/director needs to establish the best strategy for his group of individuals. Often practising different strategies can give an indication of what works best.

Video highlights and live coverage links